Definition:

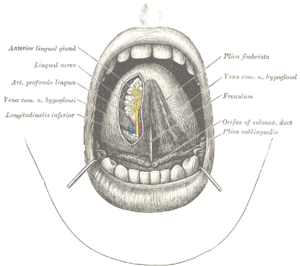

By definition, complete ankyloglossia is the total adherence of the tongue to the floor of the mouth. Partial ankyloglossia is incomplete separation of the tongue from the bottom of the mouth due to a short frenulum, which is a fibrous membrane extending from the bottom of the tongue to an area below the bottom front teeth. Tongue-tie can be evident when the baby is crying or by careful inspection.

CLICK TO SEE THE PICTURES…..>….(01)....(1).…..….(2)..……...(3)..……..…………..

Symptoms:

There are certain facial features that have been found to be associated with a short frenulum.

*High-arched palate: characterized by a higher than normal arch of the roof of the mouth.

*Retrognathia: very small chin.

*Micrognathia: a recessed or undefined chin.

*Prognathism: a protruding lower jaw.

*Can’t stick the tongue forward

*Difficulty feeding

*Excessive attachment of tongue to bottom of the mouth

*V-shaped notch in tip of tongue

Causes:

Tongue-tie causes a significant portion of of the problems encountered with breastfeeding. It also is thought to pose other short term and long term complications, such as speech impediments, problems with swallowing, and the formation of teeth arrangement. There is some controversy over the defining characteristics of tongue-tie as well as the treatments.

When we hear the term “tongue-tied”, most of us have a mental image of someone who is struggling to speak in public, but is stammering nervously and is at a loss for words. In reality, tongue-tie is a medical condition that affects many people, and has special implications for the breastfed baby.

The medical term for the condition known as tongue-tie is “ankyloglossia”. It results when the frenulum (the band of tissue that connects the bottom of the tongue to the floor of the mouth) is too short and tight, causing the movement of the tongue to be restricted.

Tongue-tie is congenital (present at birth) and hereditary (often more that one family member has the condition). It occurs relatively often: between 0.2% and 2% of babies are born with tight frenulums.

To tell if your baby is tongue-tied, look at him and stick out your tongue. Even tiny babies will imitate you. If he is unable to extend his tongue fully, or if it has a heart shaped appearance on the tip, then you should have him evaluated by his doctor. You can also try putting your finger in his mouth (pad side up) until he starts sucking. See if his tongue extends over his gum line to cup the bottom of your finger. If not, you may want to have him checked.

In most cases, the frenulum recedes on its own during the first year, and causes no problems with feeding or speech development. A lot depends on the degree of the tongue-tie: if the points of attachment are on the very tip of the tongue and the top ridge of the bottom gum, feeding and speech are more likely to be affected than if the frenulum is attached further back.

Severe tongue-tie can cause problems with speech. Certain sounds are difficult to make if the tongue can’t move freely (especially ‘th’, ‘s’, ‘d’, ‘l’, and ‘t’). In addition to forming specific sounds, tongue-tie may also make it hard for a child to lick an ice cream cone, stick out his tongue, play a wind instrument, or French kiss. While these may not seem like important skills to you as a new mother, someday they may be very important to your child! Dental development may also be affected, with severe tongue- tie sometimes causing a gap between the two lower front teeth.

Of more immediate importance is the negative impact that a tight frenulum can have on a baby’s ability to breastfeed effectively. In order to extract milk from the breast, the baby needs to move his tongue forward to cup the nipple and areola, drawing it back in his mouth and pressing the tissue against the roof of his mouth. This compresses the lactiferous sinuses (the pockets behind the areola where the milk is stored) and allows the milk to move into the baby’s mouth. The tongue plays an important role in breastfeeding, and if the baby’s frenulum is so short that his tongue can’t extend over the lower gum, he may end up compressing the breast tissue between his gums while he nurses, which can cause severe damage to the nipples.

Tongue-tie can cause feeding difficulties such as low weight gain and constant fussiness in the baby. Nursing mothers may experience nipple trauma (the pain doesn’t go away no matter what position is used), plugged ducts, and mastitis.

Some tongue-tied babies are able to nurse effectively, depending on the way the frenulum is attached, as well as the individual variations in the mother’s breast. If the mother has small or medium nipples, the baby may be able to manage to extract the milk quite well in spite of being tongue-tied. On the other hand, if the nipples are large and/or flat, then even a slight degree of tongue-tie may cause problems for a nursing baby.

In addition to problems with nipple soreness and weight gain, some other signs that the baby may be having problems nursing effectively include breaking suction often during feedings, and making a clicking sound while nursing. Since these symptoms can also be caused by other problems, it’s a good idea to be evaluated by a knowledgeable health care provider (a lactation consultant if possible) to rule out causes other than tongue-tie. Tongue-tie should definitely be considered a possibility if breastfeeding doesn’t improve even after other measures such as adjustments in positioning have been tried.

If it is determined that tongue-tie is causing breastfeeding difficulties, there is a simple procedure called a “frenetomy” that can quickly correct the problem. In a relatively painless in-office procedure, the doctor simply clips the frenulum to loosen it and allow the tongue full range of motion. It takes less than a second, and because the frenulum contains almost no blood, there is usually only a drop or two of blood. The baby is put on the breast immediately following the procedure, and the bleeding stops almost instantly. Anesthesia and stitches are not necessary. The baby cries more because he is being restrained for a few seconds that he does because of pain. Comparing the procedure to ear piercing is a good analogy. Both involve a second or two of discomfort and a very small risk of infection, but are overall very safe and simple procedures.

Diagnosis

According to Horton et al., diagnosis of ankyloglossia may be difficult; it is not always apparent by looking at the underside of the tongue but is often dependent on the range of movement permitted by the genioglossus muscles. For infants, passively elevating the tongue tip with a tongue depressor may reveal the problem. For older children, making the tongue move to its maximum range will demonstrate the tongue tip restriction. In addition, palpation of genioglossus on the underside of the tongue will aid in confirming the diagnosis.

In most cases, the mother notices an immediate improvement in both her comfort level and the baby’s ability to nurse more efficiently. If the tongue-tie isn’t identified and the frenulum isn’t clipped until the baby is several weeks or months old, then it may take longer for him to learn to suck normally. Sometimes suck training is necessary in order for him to adapt to the new range of motion of his tongue. If tongue-tie is causing severe breastfeeding difficulties, then the sooner the frenulum is clipped, the better. Sometimes children end up having the procedure done when they are much older, because the problem isn’t identified until after they begin developing significant speech problems.

Even though clipping the frenulum is a simple, safe, and uncomplicated procedure, it may be difficult to find a doctor who is willing to perform it. The history of treating tongue-tie is somewhat controversial. Up until the nineteenth century, baby’s frenulums were clipped almost routinely. Because of the potential for feeding and speech problems, midwives were reported to keep one fingernail sharpened so that they could sweep under the tongue and snip the frenulum of just about all newborn babies. Any procedure that involves cutting tissue in the mouth can potentially involve infection or damage to the tongue, especially back in the days before sterile conditions and antibiotics. Because the procedure was overdone and in most cases, wasn’t really necessary, doctors became very reluctant to clip frenulums at all and the procedure was rarely performed.

Part of the reason frenotomies fell out of favor for many years was the fact that doctors discovered that in all but the most severe cases, speech was not affected by tongue-tie. They preferred to take a “wait and see” approach and let nature take it’s course. Most of the time, the frenulum would stretch out on its own with no intervention.

During the same time period that frenotomies were becoming less common, the rate of breastfeeding also declined dramatically. Bottle-feeding doesn’t present the same feeding difficulties for tongue-tied babies that breastfeeding does, because the mechanics are very different and extension of the tongue doesn’t play as big a role in feeding from the bottle. Since the majority of babies were bottle fed, it was easy for doctors to say that they weren’t going to perform an unnecessary procedure that didn’t interfere with feeding, and rarely caused speech problems.

Even today, with most infants in this country starting out breastfeeding, it may be difficult to find a doctor who recognizes the problem that tongue-tie can present for a nursing baby and is willing to perform a frenotomy. The procedure is seldom mentioned in the pediatric literature, and is no longer routinely taught in medical school.

If you feel that your baby’s breastfeeding difficulties may be due to tongue-tie, you may need to work at finding a health care provider who can diagnose the problem and clip the frenulum. Although any pediatrician or general family practitioner can theoretically perform a frenotomy, many prefer to make a referral to an oral surgeon, dentist, or ENT specialist.

Diagnosis of Clinically Significant Tongue-Tie

Based on a combination of anatomical appearance and functional disturbance:

Anatomical Type I: Frenulum attaches to tip of tongue in front of alveolar ridge in low lip sulcus….

Type II: Attaches 2-4mm behind tongue tip and attaches on alveolar ridge…..click for picture.

Type III: Attaches to mid-tongue and middle of floor of the mouth, usually tighter and less elastic. The tip of the tongue may appear “heart-shaped”

Type IV: Attaches against base of tongue, is shiny, and is very inelastic

Effects:-

Ankyloglossia can affect feeding, speech, and oral hygiene as well as have mechanical/social effects. Ankyloglossia can also prevent the tongue from contacting the anterior palate. This can then promote an infantile swallow and hamper the progression to an adult-like swallow which can result in an open bite deformity. It can also result in mandibular prognathism; this happens when the tongue contacts the anterior portion of the mandible with exaggerated anterior thrusts. The authors sent a survey to a total of 1598 otolaryngologists, pediatricians, speech-language pathologists and lactation consultants with questions to ascertain their beliefs on ankyloglossia; 797 of the surveys were fully completed and used in the study. It was found that 69 percent of lactation consultants but only a minority of pediatricians answered that ankyloglossia is frequently associated with feeding difficulties; 60 percent of otolaryngologists and 50 percent of speech pathologists answered that ankyloglossia is sometimes associated with speech difficulties compared to only 23 percent of pediatricians; 67 percent of otolaryngologists compared to 21 percent of pediatricians answered that ankyloglossia is sometimes associated with social and mechanical difficulties. Limitations of this study include a reduced sample size due to unreturned or incomplete surveys.

Feeding

Messner et al. studied ankyloglossia and infant feeding. Thirty-six infants with ankyloglossia were compared to a control group without ankyloglossia. The two groups were followed for six months to assess possible breastfeeding difficulties, defined as nipple pain lasting more than six weeks, or infant difficulty latching onto or staying onto the mother’s breast. Twenty-five percent of mothers of infants with ankyloglossia reported breast feeding difficulty compared with only 3 percent of the mothers in the control group. The study concluded that ankyloglossia can adversely affect breastfeeding in certain infants. Infants with ankyologlossia do not, however, have such big difficulties when feeding from a bottle. Limitations of this study include the small sample size and the fact that the quality of the mother’s breast feeding was not assessed.

Wallace and Clark also studied breastfeeding difficulties in infants with ankyloglossia.[8] They followed 10 infants with ankyloglossia who underwent surgical tongue tie division. Eight of the ten mothers experienced poor infant latching onto the breast, 6/10 experienced sore nipples and 5/10 experienced continual feeding cycles; 3/10 mothers were exclusively breastfeeding. Following a tongue tie division, 4/10 mothers noted immediate improvements in breastfeedings, 3/10 mothers did not notice any improvements and 6/10 mothers continued breastfeeding for at least four months after the surgery. The study concluded that tongue tie division may be a possible benefit for infants experiencing breastfeeding difficulties due to ankyloglossia and further investigation is warranted. The limitations of this study include that the sample size was small and that there was not a control group. In addition, the conclusions were based on subjective parent report as opposed to objective measures.

Speech

Messner and Lalakea studied speech in children with ankyloglossia. They noted that the phones likely to be affected due to ankyloglossia include sibilants and lingual sounds such as [t d z s ? ð n l]. In addition, the authors also state that it is uncertain as to which patients will have a speech disorder that can be linked to ankyloglossia and that there is no way to predict at a young age which patients will need treatment. The authors studied 30 children from one to 12 years of age with ankyloglossia, all of whom underwent frenuloplasty. Fifteen children underwent speech evaluation before and after surgery. Eleven patients were found to have abnormal articulation before surgery and nine of these patients were found to have improved articulation after surgery. Based on the findings, the authors concluded that it is possible for children with ankyloglossia to have normal speech in spite of decreased tongue mobility. However, according to their study, a large percent of children with ankyloglossia will have articulation deficits that can be linked to tongue tie and these deficits may be improved with surgery. The authors also note that ankyloglossia does not cause a delay in speech or language but, at the most, problems with enunciation. Limitations of the study include a small sample size as well as a lack of blinding of the speech-language pathologists who evaluated the subjects’ speech.

Messner and Lalakea also examined speech and ankyloglossia in another study. They studied 15 patients and speech was grossly normal in all of the subjects. However, half of the subjects reported that they thought that their speech was more effortful than other peoples’ speech.

Horton et al. discussed the relationship between ankyloglossia and speech. The authors believe that tongue tie contributes to difficulty in range and rate of articulation and that compensation is needed. Compensation at its worst, the article states, may involve a Cupid’s bow of the tongue.

While the tongue tie exists, and even years after removal, common speech abnormalities include mispronunciation of words. The most common is pronouncing Ls as Ws; for example the word “lemonade” would come out as “wemonade.”

Mechanical/Social

Ankyloglossia can result in mechanical and social effects. Lalakea and Messner studied 15 people, aged 14 to 68 years. The subjects were given questionnaires in order to assess functional complaints associated with ankyloglossia. Eight subjects noted one or more mechanical limitations which included cuts or discomfort underneath the tongue and difficulties with kissing, licking one’s lips, eating an ice cream cone, keeping one’s tongue clean and performing tongue tricks. In addition, seven subjects noted social effects such as embarrassment and teasing. The authors concluded that this study confirmed anecdotal evidence of mechanical problems associated with ankyloglossia and that it suggests that the kinds of mechanical and social problems noted may be more prevalent than previously thought. Furthermore, the authors note that some patients may be unaware of the extent of the limitations they have due to ankyloglossia since they have never experienced normal tongue range. A limitation of this study is the small sample size that also represented a large age range.

Lalakea and Messner note that mechanical and social effects may occur even without other problems related to ankyloglossia such as speech and feeding difficulties. Also, mechanical and social effects may not arise until later in childhood as younger children may be unable to recognize or report the effects. In addition, some problems may not come about until later in life, such as kissing.

Complications

The complications are rare, but recurrence of tongue tie, tongue swelling, bleeding, infection, and damage to the ducts of the salivary glands may occur.

Treatment:

Surgery is seldom necessary but if it is needed, it involves cutting the abnormally placed tissue. If the child has a mild case of tongue tie, the surgery may be done in the doctor’s office. More severe cases are done in a hospital operating room. A surgical reconstruction procedure called a z-plasty closure may be required to prevent scar tissue formation.

Prognosis:

Surgery, if performed, is usually successful.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to be a substitute for professional medical advise or help. It is always best to consult with a Physician about serious health concerns. This information is in no way intended to diagnose or prescribe remedies.This is purely for educational purpose.

Resources:

http://tonguetie.ballardscore.com/

http://www.breastfeeding-basics.com/html/tonguetie.shtml

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ankyloglossia

http://www.righthealth.com/topic/Tongue_Tie_Treatment/overview/adam20?fdid=Adamv2_001640§ion=Full_Article

http://www.blueskydentaloffice.com/Children_s_Dentistry.html

Related articles by Zemanta

- Treating tongue tie could help more babies breastfeed (scienceblog.com)

- Treating tongue tie could help more babies breastfeed (eurekalert.org)

- Simple snip could help more babies breastfeed (holykaw.alltop.com)

- Does a lover really have first claim on breasts? (telegraph.co.uk)

- 10 Tips on Successful Breastfeeding (globalthoughtz.com)

- You: The truth about babies, by Zoe Williams (guardian.co.uk)

- Some Health Quaries & Answers (findmeacure.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?w=580)