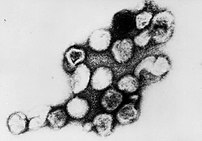

Image via Wikipedia

Definition:

Rubella — commonly known as German measles or 3-day measles — is an infection that primarily affects the skin and lymph nodes. It is caused by the rubella virus (not the same virus that causes measles), which is usually transmitted by droplets from the nose or throat that others breathe in. It can also pass through a pregnant woman‘s bloodstream to infect her unborn child. As this is a generally mild disease in children, the primary medical danger of rubella is the infection of pregnant women, which may cause congenital rubella syndrome in developing babies.

It is a disease caused by Rubella virus. The name is derived from the Latin, meaning little red. Rubella is also known as German measles because the disease was first described by German physicians in the mid-eighteenth century. This disease is often mild and attacks often pass unnoticed. The disease can last one to five days. Children recover more quickly than adults. Infection of the mother by Rubella virus during pregnancy can be serious; if the mother is infected within the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, the child may be born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), which entails a range of serious incurable illnesses. Spontaneous abortion occurs in up to 20% of cases.

Rubella is a common childhood infection usually with minimal systemic upset although transient arthropathy may occur in adults. Serious complications are very rare. If it were not for the effects of transplacental infection on the developing foetus, rubella is a relatively trivial infection.

Acquired, (i.e. not congenital), rubella is transmitted via airborne droplet emission from the upper respiratory tract of active cases. The virus may also be present in the urine, faeces and on the skin. There is no carrier state: the reservoir exists entirely in active human cases. The disease has an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks.

In most people the virus is rapidly eliminated. However, it may persist for some months post partum in infants surviving the CRS. These children were an important source of infection to other infants and, more importantly, pregnant female contacts

Before a vaccine against rubella became available in 1969, rubella epidemics occurred every 6 to 9 years. Kids ages 5 to 9 were primarily affected, and many cases of congenital rubella occurred as well. Now, due to immunization of children, there are much fewer cases of rubella and congenital rubella.

Most rubella infections today appear in young, non-immunized adults rather than children. In fact, experts estimate that 10% of young adults are currently susceptible to rubella, which could pose a danger to any children they might have someday.

Signs and Symptoms:

After an incubation period of 14-21 days, the primary symptom of rubella virus infection is the appearance of a rash (exanthem) on the face which spreads to the trunk and limbs and usually fades after three days. Other symptoms include low grade fever, swollen glands (post cervical lymphadenopathy), joint pains, headache, conjunctivitis. The swollen glands or lymph nodes can persist for up to a week and the fever rarely rises above 38 oC (100.4 oF). The rash disappears after a few days with no staining or peeling of the skin. Forchheimer’s sign occurs in 20% of cases, and is characterized by small, red papules on the area of the soft palate.

Rubella can affect anyone of any age and is generally a mild disease, rare in infants or those over the age of 40. The older the person is the more severe the symptoms are likely to be. Up to one-third of older girls or women experience joint pain or arthritic type symptoms with rubella. The virus is contracted through the respiratory tract and has an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks. During this incubation period, the carrier is contagious but may show no symptoms.

The rubella rash can look like many other viral rashes. It appears as either pink or light red spots, which may merge to form evenly colored patches. The rash can itch and lasts up to 3 days. As the rash clears, the affected skin occasionally sheds in very fine flakes.

Other symptoms of rubella, which are more common in teens and adults, may include: headache; loss of appetite; mild conjunctivitis (inflammation of the lining of the eyelids and eyeballs); a stuffy or runny nose; swollen lymph nodes in other parts of the body; and pain and swelling in the joints (especially in young women). Many people with rubella have few or no symptoms at all.

When rubella occurs in a pregnant woman, it may cause congenital rubella syndrome, with potentially devastating consequences for the developing fetus. Children who are infected with rubella before birth are at risk for growth retardation; mental retardation; malformations of the heart and eyes; deafness; and liver, spleen, and bone marrow problems.

Congenital Rubella Syndrome:

Rubella can cause congenital rubella syndrome in the newly born. The syndrome (CRS) follows intrauterine infection by Rubella virus and comprises cardiac, cerebral, ophthalmic and auditory defects. It may also cause prematurity, low birth weight, and neonatal thrombocytopenia, anaemia and hepatitis. The risk of major defects or organogenesis is highest for infection in the first trimester. CRS is the main reason a vaccine for rubella was developed. Many mothers who contract rubella within the first critical trimester either have a miscarriage or a still born baby. If the baby survives the infection, it can be born with severe heart disorders (PDA being the most common), blindness, deafness, or other life threatening organ disorders. The skin manifestations are called “blueberry muffin lesions.

Cause:

The disease is caused by Rubella virus, a togavirus that is enveloped and has a single-stranded RNA genome. The virus is transmitted by the respiratory route and replicates in the nasopharynx and lymph nodes. The virus is found in the blood 5 to 7 days after infection and spreads throughout the body. It is capable of crossing the placenta and infecting the fetus where it stops cells from developing or destroys them.

The cause of rubella is a virus that’s passed from person to person. It can spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes, or it can spread by direct contact with an infected person’s respiratory secretions, such as mucus. It can also be transmitted from a pregnant woman to her unborn child. A person with rubella is contagious from one week before the onset of the rash until about one to two weeks after the rash disappears.

Rubella is rare in the United States because most children receive a vaccination against the infection at an early age. However, cases of rubella do occur, mostly in unvaccinated foreign-born adults.

The disease is still common in many parts of the world, although more than half of all countries now use a rubella vaccine. The prevalence of rubella in some other countries is something to consider before going abroad, especially if you’re pregnant.

Contagiousness:

The rubella virus passes from person to person through tiny drops of fluid from the nose and throat. People who have rubella are most contagious from 1 week before to 1 week after the rash appears. Someone who is infected but has no symptoms can still spread the virus.

Infants who have congenital rubella syndrome can shed the virus in urine and fluid from the nose and throat for a year or more and may pass the virus to people who have not been immunized.

Diagnosis:

Rubella virus specific IgM antibodies are present in people recently infected by Rubella virus but these antibodies can persist for over a year and a positive test result needs to be interpreted with caution. The presence of these antibodies along with, or a short time after, the characteristic rash confirms the diagnosis.

Complications:

Rubella is a mild infection. Once you’ve had the disease, you’re usually permanently immune. About 70 percent of adult women with rubella experience arthritis in the fingers, wrists and knees, which generally lasts for about one month. In rare cases, rubella can cause an ear infection (otitis media) or inflammation of the brain (encephalitis).

However, if you’re pregnant when you contract rubella, the consequences for your unborn child may be severe. Up to 85 percent of infants born to mothers who had rubella during the first 11 weeks of pregnancy develop congenital rubella syndrome. This can cause one or more problems, including growth retardation, cataracts, deafness, congenital heart defects and defects in other organs. The highest risk to the fetus is during the first trimester, but exposure later in pregnancy also is dangerous.

Fortunately, an average of fewer than 10 babies are born with congenital rubella syndrome in the United States each year. Rubella occurs most frequently in adults who never received vaccinations because they came from other countries where the MMR vaccine isn’t widely used.

Modern Treatment:

Rubella cannot be treated with antibiotics because antibiotics do not work against viral infections. Unless there are complications, rubella will resolve on its own.

Any pregnant woman who has been exposed to rubella should contact her obstetrician immediately.

Symptoms are usually treated with paracetamol until the disease has run its course. Treatment of newly born babies is focused on management of the complications. Congenital heart defects and cataracts can be corrected by surgery. Management for ocular CRS is similar to that for age-related macular degeneration, including counseling, regular monitoring, and the provision of low vision devices, if required.

Home Treatment:

Rubella is typically a mild illness, especially in kids. Infected children usually can be cared for at home. Monitor your child’s temperature, and call the doctor if the fever climbs too high.

To relieve minor discomfort, you can give your child acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Avoid giving aspirin to a child who has a viral illness because its use in such cases has been associated with the development of Reye syndrome, which can lead to liver failure and death.

Prognosis:

Rubella infection of children and adults is usually mild, self-limiting and often asymptomatic. The prognosis in children born with CRS is poor.

Self-care:

In rare instances when a child or adult is infected with rubella, simple self-care measures are required:

* Rest in bed as necessary.

* Take acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) to relieve discomfort from fever and aches.

* Tell friends, family and co-workers — especially pregnant women — about your diagnosis if they may have been exposed to the disease.

Don’t give aspirin to children who have a viral illness. Aspirin in children has been associated with Reye’s syndrome — a rare, but serious illness that can affect the blood, liver and brain of children and teenagers after a viral infection

Epidemiology:

Rubella is a disease that occurs worldwide. The virus tends to peak during the spring in countries with temperate climates. Before the vaccine to rubella was introduced in 1969, widespread outbreaks usually occurred every 6-9 years in the United States and 3-5 years in Europe, mostly affecting children in the 5-9 year old age group. Since the introduction of vaccine, occurrences have become rare in those countries with high uptake rates. However, in the UK there remains a large population of men susceptible to rubella who have not been vaccinated. Outbreaks of rubella occurred amongst many young men in the UK in 1993 and in 1996 the infection was transmitted to pregnant women, many of whom were immigrants and were susceptible. Outbreaks still arise, usually in developing countries where the vaccine is not as accessible.

During the epidemic in the US between 1962-1965, Rubella virus infections during pregnancy were estimated to have caused 30,000 still births and 20,000 children to be born impaired or disabled as a result of CRS. Universal immunisation producing a high level of herd immunity is important in the control of epidemics of rubella.

Prevention:

Rubella infections are prevented by active immunisation programs using live, disabled virus vaccines. Two live attenuated virus vaccines, RA 27/3 and Cendehill strains, were effective in the prevention of adult disease. However their use in prepubertile females did not produce a significant fall in the overall incidence rate of CRS in the UK. Reductions were only achieved by immunisation of all children.

The vaccine is now given as part of the MMR(measles-mumps-rubella ) vaccine. The WHO recommends the first dose is given at 12 to 18 months of age with a second dose at 36 months. Pregnant women are usually tested for immunity to rubella early on. Women found to be susceptible are not vaccinated until after the baby is born because the vaccine contains live virus.

The immunization program has been quite successful with Cuba declaring the disease eliminated in the 1990s. In 2004 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that both the congenital and acquired forms of rubella had been eliminated from the United States.

History:

Rubella was first described in the mid-eighteenth century. Friedrich Hoffmann made the first clinical description of rubella in 1740, which was confirmed by de Bergen in 1752 and Orlow in 1758.

In 1814, George de Maton first suggested that it be considered a disease distinct from both measles and scarlet fever. All these physicians were German, and the disease was known as Rötheln (from the German name Röteln), hence the common name of “German measles”. Henry Veale, an English Royal Artillery surgeon, described an outbreak in India. He coined the name “rubella” (from the Latin, meaning “little red”) in 1866.

It was formally recognised as an individual entity in 1881, at the International Congress of Medicine in London. In 1914, Alfred Fabian Hess theorised that rubella was caused by a virus, based on work with monkeys. In 1938, Hiro and Tosaka confirmed this by passing the disease to children using filtered nasal washings from acute cases.

In 1940, there was a widespread epidemic of rubella in Australia. Subsequently, ophthalmologist Norman McAllister Gregg found 78 cases of congenital cataracts in infants and 68 of them were born to mothers who had caught rubella in early pregnancy. Gregg published an account, Congenital Cataract Following German Measles in the Mother, in 1941. He described a variety of problems now know as congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) and noticed that the earlier the mother was infected, the worse the damage was. The virus was isolated in tissue culture in 1962 by two separate groups led by physicians Parkman and Weller.

There was a pandemic of rubella between 1962 and 1965, starting in Europe and spreading to the United States. In the years 1964-65, the United States had an estimated 12.5 million rubella cases. This led to 11,000 miscarriages or therapeutic abortions and 20,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome. Of these, 2,100 died as neonates, 12,000 were deaf, 3,580 were blind and 1,800 were mentally retarded. In New York alone, CRS affected 1% of all births

In 1969 a live attenuated virus vaccine was licensed. In the early 1970s, a triple vaccine containing attenuated measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) viruses was introduced.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to be a substitute for professional medical advise or help. It is always best to consult with a Physician about serious health concerns. This information is in no way intended to diagnose or prescribe remedies.This is purely for educational purpose

Resources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubella

http://kidshealth.org/parent/infections/skin/german_measles.html

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/rubella/DS00332/DSECTION=1